Ronan Harris is on the crest of the electronic music wave with his tenth VNV Nation studio album “Noire”, released in October last year on his own label. The combination of danceable beats, synthpop, EBM and atmospheric pieces of classical music telling stories of grandeur have contributed to the legendary status VNV Nation righteously can claim after staying at the top of the electronic scene for more than twenty years.

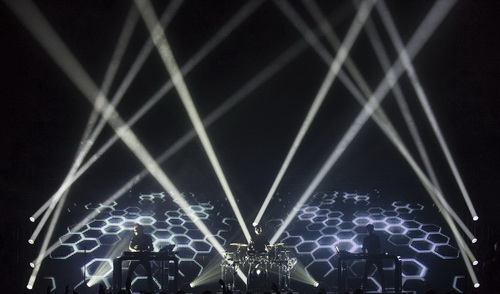

Much has changed since former album “Transnational”; Mark Jackson left in 2017 and at present VNV Nation is touring the world as a four-piece. In between the first and second leg of this world tour, we sat down with Ronan Harris in his hometown Hamburg to have an interesting chat about “Noire”, the surreal video experience in Tokyo and creative control. We learned that he has made six albums outside VNV Nation, that he hates the word futurepop and a lot more. We also took some photos, at the interview and at the concert.

An Irishman in Hamburg

The interview starts out in a brief history entailing the reason to why Ronan moved to Hamburg and how he came to be influenced by electronic music as a young lad in Ireland.

Just out of curiosity, why did you make the move to Hamburg and Germany? Was it to get closer to the electronic music scene?

- I didn’t know the language, just a little bit of German, but I wanted to go there to see how I survived.

And also I like rain. I love rain! Rain is beautiful! We Irish invented rain and exported it to the rest of Europe (laughs). It’s just this coastal thing. I grew up beside the sea, I need that, and I have to have the sea near me. The one thing about Hamburg is that the city stops and then there’s a beautiful countryside around it. You have the sea, you have forests and you have mountains nearby if you want them.

It sounds like a “Hey tourists, welcome to Hamburg” thing (laughs).

I’ve always wondered how you ended up on the electronic music scene when you grew up in Ireland. It’s not really the first music genre you associate with the country. Isn’t Ireland the land of alternative rock, associated with U2 and The Cranberries?

- As far as me, there were a lot of electronic musicians on Ireland. It’s kind of like Sweden; you have a lot of folk music, you have a lot of rock but you also did different music like Roxette or Army of Lovers. It’s just a matter of taste and what you hear and what you like.

But there were a lot of electronic music makers on Ireland and a lot of fans of it, and it was just something I grabbed onto. I don’t necessarily have to like the music that the rest of the country likes.

When did you understand that VNV Nation would be more than a hobby, something you can do for a living?

- It wasn’t a decision, it was more like I was kind of forced into it. I had a permanent job and around 1999 to 2000 I wasn’t going to be able to just take holidays to do tours; it was too much to do on top of my regular job.

I decided to take a break for a year to at least get it out of my system, have fun with it. Then the band kind of exploded and I’m still on my break but it is eighteen years later. But I didn’t choose to do that, it wasn’t what I really wanted to do. It was more out of necessity, but I was having fun and I wanted to enjoy it.

Ronan the composer

The new album “Noire” is out and yet again you have a few amazing cinematic pieces on the album. I always wanted to ask you about the future of you as a musician in terms of what you want to do. You have always worked with cinematic songs or songs with bits and pieces of classical music on every album, and when you made “Resonance” it was like you gave those pieces their own space. Have you ever thought of making a tour with an orchestra just to pay tribute to that side of VNV Nation?

- Yes of course! I’ve learned how to compose, I’ve learned how to transcribe my music that I would write but write it for an orchestra. The good thing is coming from another area is that you have a different view.

When I worked with the arrangements of “Resonance” we added some arrangements to it where we really pushed the envelope with people and said “Let’s try out something bigger and better that’s more bombastic or played with less technology”, let’s reinterpret them. So, we did “Honour” for orchestra, which has not been released, we’ve only played that live, and we did “The Farthest Star” for orchestra which is spectacular because it feels like oceanic music.

When I come from my side of things, I don’t know the rules, so I break the rules. It’s actually one of the nicest things with punk music as well; when you come from punk you don’t understand former music so you just break the rules and you push people to do things differently.

I love composing, I have a lot of other projects that I’ve done that I don’t do under my name because I don’t necessarily want to have it connected with my name because people will judge it. With the last number of years between “Resonance” and also working on “Noire”, a lot of opportunities came my way; people who wanted to work with me on film music, and I said “I’d like to work on film music but I also want to feel the film”, because if I don’t, what’s the point. I feel my own music and that’s the only language I really can speak through. I communicate through music in a way I can’t with words.

I got six albums of other projects that I’ve worked on; I’ve done dark ambient, I’ve done post classical and basically everything, and it’s all been building up to a moment where I said “OK, now explode, go”. There are some really big adventurous plans for next year; I want to do something with “Noire” that I don’t think anyone would expect.

The arrangement of “Nocturne No.7” on “Noire” and collaborating with Simon Jakubowski feels like you take another step towards a classical sound.

- I did a classical version of “Further” as well. The only thing is that Simon is an incredible pianist and I said “Come in and play”, and that’s it. I sat in a studio one day and I just started playing, playing and playing, and I thought “What the hell is going on? Do you feel like you’re channeling something?”.

Originally it was fifteen minutes of me just playing – it’s a story! The musical language of, let’s say, the late 1800th is that every piece of music is telling kind of a musical story; it’s not a picture story, maybe it creates pictures for someone, but you know what passage happens and how it should turn and that’s something about music we’ve lost, we don’t understand that language anymore.

I’ve been in love with classical music since I was five years old and I’ve always loved it alongside so many other styles of music. Writing a nocturne belong to an album called “Noire” because if anything, on an album that has taken its inspiration from different interpretations of the night and what the night can bring about inside you, it seems completely relevant.

If someone asked me why it was on there I’d say “Well, in a way I guess it’s because I want it on there”, and in another way, if it was not on there, it would be me saying “I don’t want to answer questions from people why that piece is on there”. But I don’t care what some people would think, I hope that some people would get what the flow of the album is.

No rules

Interesting because I hear that from very few bands today that the album should tell a story, it’s rather about having a few singles and fill up an album. But I also read some of the first reviews on “Noire” that complain about “too many instrumental songs” on the album. How much do such reviews affect you?

- I don’t care, I really don’t care because they are a minority, because the album reviews I’ve seen, and even the fan reaction, are really good.

What’s a fan? Is it someone out of a scene who says “Here are the rules of this scene and if you don’t follow these rules we don’t like your album”. I don’t make music for people like that, I don’t care about them. There will always be negative comments. There were people who commented that there were no songs that were 140 BPM, and I’m like “What!? There never are anymore! There haven’t been since 2001”.

It’s fun that you say it though because we [me and the photographer] talked about the two main sides of VNV Nation on the way here, that you have both the upbeat, danceable side and the more cinematic side of music, and that’s the strength of what you do. Someone also said you’re the pioneer of futurepop.

- I hate that word [laughs]! But there’s not even just two sides; there’s a post-rock track on “Transnational” called “Teleconnect, Pt.2”, there are orchestral pieces, there are ambient/electronic pieces or more experimental pieces and there are rock pieces whether they have drums or not. They can sometimes be very synthpoppy, they can at times be some kind of a Social Distortion track. I just don’t believe in being limited and just don’t want to reduce to just those two sides.

These instrumental or classical inspired pieces is just one part of a wider palette. Someone asked me about the words “All Our Sins”, the final track of the album, and they didn’t understand why the song sounds the way it does and I said “I wrote these words, I had them in my head. And I have written a melody on the computer and this is what I want to sing, how I want to express it. I can hear the emotion in my head”. The music was written to it to be the correct vessel to convey those words, it wasn’t the other way around. And they didn’t understand that!

If some people like it because they hear “Nova” and think “I want more ‘Nova’“, then that’s great but that’s not how I feel about making music; it’s whatever I’m letting out, it’s whatever I’m feeling at the time.

But have you ever thought of releasing a completely orchestrated album, just like Midge Ure did two years ago?

- I had exactly the same question in an interview before this and I said “On my very first album I had tons of orchestral pieces, on my second album the same. Every single album has had orchestral influences.

This album I wrote to myself never to be released, called “Praise the Fallen” from 1998, I wrote it and recorded it in 1997 and it was inspired by music from Mahler and Dvořák, two great composers. It’s this orchestral sort of hard electronic music and then there are these quiet pieces, but it’s not that they are filling space. And that’s how I think that people are listening to music.

Let’s say that you’re going to listen to drum’n’bass, you’re going to expect that it’s all going to be drum’n’bass so if there’s something without any drums you will think “Oh, that’s not drum’n’bass, it’s just there to be a long nice intro”, but I’ve never written music like that.

For example, with “A Million” [opening track on “Noire”] it was the weirdest process; I knew how it would start, I knew how it would end, and everything went automatically. I just knew what I had to, when and where, and it was the weirdest experience. My assistant producer, who tweaks the sounds and plays with the mix in certain ways and helps me to save a lot of time, just said “You’re so relaxed and just sit an armchair for an hour. You just chat, laugh and joke about stuff and then you just go back in and are on it again. I never seen you like this”, and I said “A lot of things have changed but I don’t know why”.

But is it a change because you’re on your own now?

- I had a live drummer, that’s it. I really don’t want this to sound like I’m diminishing someone, I’m not. At the beginning we were a duo and it felt better that way in the photographs. I was making music alone and he [Mark] came in to assist me with a couple of shows. It became a kind of permanent relationship around 1999 but I was continuing doing the work, it was always going to be like that.

Because we also made live shows as a duo it seemed to make sense that we were presented as a duo, and I didn’t think anything of it because a lot of bands did that. The Cure did it and lots of bands did this sort of thing where they used some sort of session musicians but the same musicians because they knew the music.

In the creative process nobody has ever been involved. The only other person who has ever been with me in the studio, as far as involvement and creation is André Winter, who I started working with in 2005 but he is not writing, he’s mixing and helping out with sounds in the production and tweaking things and playing with sounds here and there. He’s a great artist on his own and a really well-known underground dance artist and has his own career. He lends his experience with how he mixes and how he twists basses and stuff like that. Like on “Automatic” I did “Control” and “Nova” and a couple of other tracks, and he was working on “Space & Time” and doing all these cuts and edits, and weird bits for me.

It’s a great because we can work in parallel where I’m the producer and can say “This is how I would like it to feel, can you give me a bit of that?” or I can tell him to give a song a certain feeling I’m looking for. We both work in parallel in our studios; I’m writing and doing full finished songs and the mixes and arrangements and everything. He will come in and give me advice, but no one else has ever been involved in the creative process.

I’m explaining that to people, and I thought it was obvious because I was writing it in the credits the whole time for years and I never thought about it, it was just that we were presented as a duo until 2005 but we never saw each other outside the concerts, we barely talked on the phone. The only time we really had any contact was at concerts.

Mark has hit pads in the past and what changed is that Basti came in and he is a monster drummer, he is just an insane drummer, and nobody feels like a hired hand, we actually feel that we got a little gang (laughs). This is the most I felt like a band ever.

The shortest Tokyo trip ever

You finally made your video debut with “When Is the Future?”. Why does it happen now?

- Have you ever seen that shit that video companies send you back when you ask them for a video? I don’t want a video, I want a video that at least conveys the message of the song. I have over the years gotten back some of the most fucking ridiculous treatments from video companies where I just thought “How the fuck are you keeping a customer?”.

They were writing ideas where I had to say “Did you read the brief what the song is about?”; they basically just pulled something out of the drawer that they wrote four years ago and thought “Maybe they’ll take this idea and pay us for it”. Some of them were just embarrassing.

I don’t really want to do a video if it doesn’t help the song; I don’t want to take anything away from the song. That was one of the reasons why it should be as it is. It’s not going to be that you don’t even think about the song and just watch the video.

Is anyone thinking about “Where is this great future we’re planning for ourselves?”? We all talked about how the future is going to be and it’s going to be marvelous and awesome – and we’re all afraid of it! We’re afraid that tomorrow is going to be shittier than today, and I kind of thought “No, this is not what I grew up with”. I do believe we have the ability to change everything and make everything amazing on this planet and find a way that works for everybody. We were just caught by a virus expressed in that some people like to make shitloads of money and everyone else has been trained to follow.

First official video; two weeks before we did it somebody gave me a list of video people and said “Are you interested in having a video?”, and I said “Well, I had said that I was”. I talked to this people online and talked to them on the phone, and they seemed so super energetic, and I saw their work including work they didn’t show on their website and said “You guys really have something, you got a great vibe, and you got a feeling for things”.

And this was the week before we did the video; I said “What’s the budget for this?” and they just got back to “We’re going to Tokyo”, and I was “What the fuck? Really?”. We literally booked the flight on the Friday, I flew on Tuesday, they flew the day before and filmed loads of impressions, and I landed on Wednesday morning Tokyo time. I slept for about four hours and then filmed all that night in the pouring rain, and if you ever wondered what it’s like to be in the first “Blade Runner” movie, be in Tokyo at night in Shinjuku. It is insane; everything makes noises, everything’s playing melodies, everything’s got little animated voices.

Just picture thousands of people coming streaming out of the subway with their plastic umbrellas, and I thought that the only thing that’s missing is the little siren saying “Move on, move on” (laughs). When you were looking up, there were these billboards on the sides of buildings with LED screens playing new games and I just thought “Jesus, this is the dark future that we’re in”. It’s me as a stranger in a strangeland.

And it was just buzzing! Everything was just so electric, everyone’s talking, everyone’s running in all directions – it was so much energy and life going on. There were neon signs all over the place and it was just crazy! It was like a scene out of a book or like I’m in my own movie, and that’s the kind of feeling I channel. This is what we imagined in the early eighties when we tried to picture the world in 2017. And here we are, we have it!

As I said, I arrived on Wednesday morning and on Thursday night I flew home, that was my entire trip to Japan, and all of that was spent on walking through every area of Tokyo.

Artistic control for survival

As a music researcher I found that for most “successful” bands that have lasted long enough on the music scene to earn an iconic status, it’s in the pursuit of complete artistic freedom – and legal protections for that freedom – that will make up a significant portion of their legacies. Confrontations with record companies, streaming services, video producers and social media users inspire other artists to both demand artistic freedom and earn their fair share of profits.

There’s numerous stories of major artists having several notable fights with the music institutions that often have different views about how to run a career. But who knows better than the creator? It is important that artists reflect on the artistic vision and what that represents.

In the beginning of the 2000:s Ronan Harris gained complete creative control of his works when he started his label Anachron Sounds, thus taking control of the whole process of his output. And it hasn’t come with a huge increase in workload.

Quite much has happened in the music industry since you released ”Advance & Follow”. How do you experience the transition to the digital music age and how it has affected to work with VNV Nation?

- People want it for free. Anyone who starts giving me lectures about “But this is how bands distribute music now” just tell me “I want it for free”.

I regard Spotify as the Netflix with music and because of that I think that over the next ten years you’re going to see that the budget available to people for creative projects is going to get smaller and smaller, and they’re going to do it for fun and love.

You have people telling you how you should be making music but they don’t talk about the fact that the reason they want it like that is that they want it for free. Who are the big shareholders of the streaming businesses and why do they make this a big thing? And they say “It’s against copyright”. Really? They could have solved all the downloading if they really wanted to. They can solve everything else. And if you have politicians; most of them don’t even understand anything outside of a couple of crappy pop albums they’ve heard. They listen to easy listening or they don’t care about music at all.

Is it also one of the major reasons why you started your own label?

- You have to if you’re going to survive. Having an assistant during the actual album process is the only time I really need someone. I’ve entrusted decisions to people in the past but if they don’t get the vision of what I’m trying to do, there’s no point in having somebody there. I’ve had people working with me in the past that didn’t get it and I ended up doing the job twice.

I do the graphics or coordinate the people who are doing the graphics for me because I know how I want it to look like and I know the standard I want to have, so I’m creating something much bigger than just an album – I want it to feel a certain way.

But it isn’t actually a huge amount of work when you think about that I’m a single artist on a label, although it’s my own label. I’ve always been doing my own graphics, I’ve always been doing my own music, the only thing that has changed is that I have my own studio and I can do whatever I want. I kind of got forced into having my own label; somebody said to “Why don’t you do it? It’s a business model that works great and you can do this now – it’s 2002! Get a distributor, call yourself a label and we’ll help you”.

Making an album is a very expensive thing, making all of this is very expensive. I don’t even want to tell you what “Resonance” cost but it was not cheap, and you don’t pay buttons for an orchestra. If we lived in a streaming world, I can tell you this much: “Resonance” would not been possible, or none of this would be possible.

Then everyone says “Ah, but person X and person Y are making money just sitting on YouTube playing video games or something, or having millions of streams on Spotify”. I say “You’re talking about the one percent of the entertainment industry which is backed by big players who want to make money out of them because where people smell money, they would do everything to make money out of you”.

Take a band like The Buzzcocks; nobody wanted to sign them and they became one of the most influential punk bands ever. Their drummer was like a metronome, that man was amazing! You could time the man with an atomic clock! The thing is that bands like that were able to support themselves through small labels.

I looked back as far as the 1920:s when there was the crash [economic depression] to find out why we even have a music industry today, and do you know why we have a music industry today? Because the jukebox happened and brought music to everybody, just like the Internet is doing today.

The thing about the jukebox was that the major labels said “We’ll put the money into it” and they asked the film industry if they could use their distribution network, and the film industry said “Hey, great! How would this work?”. “Our best song-writers will make songs for you and you can put them into your movies”. Then everyone would want to buy that song [the audience] – a brilliant idea! They all shook hands and stroke their moustaches and their long beards, and they put jukeboxes in every place they could. Everybody could hear music, the new songs, and really access music leading to that they bought songs.

We’ve had the same thing and had a great time writing along on the tales of the major label industry, and then the major label industry decided to shake us off because they wanted everyone to go streaming, then they can control the product. Who knows what their plan is?

To be honest, I feel digital because I come from a technological background and I’ve also been an avid futurist since I was a teenager, theorizing about how technology will go, and I honestly have the feeling that the streaming concept, this business model, is a stopgap. This is somehow bridging something which is coming and I can’t tell yet what.

Another topic on that; part of the new music age, just like in the overall society, is to promote yourself as much as possible in social media, and that on its own just adds lots of work to what you already do. How much of a struggle is it to keep up with social media and the excessive amount of self-promotion that’s made possible? Or is it a struggle?

- What I’ve noticed is that people have always been able to tell the difference between honesty and horseshit. When bands talk to me and say “Why don’t you post on Instagram every day?” I say “Of what? Oh, here’s a picture of the table backstage. Here’s the pudding I’m having for dinner.”

It’s meaningless, it’s garbage! It may belong to bands that are meaningless. You use social media for what you want; if you want to use it in vapid and superficial ways, do it. But you also use it for what you want to say and how you want to say it.

I think there’s a lot of bands who are left behind and don’t understand it. I’ve waited for this age of wonder, this future, and I’m kind of surprised that people are doing the things with it that they are doing. You have the world of information at the fingertips on your phone and yet we have become more stupid that we care more about celebrity horseshit than we do about actual things that matter. I was hoping we were going in a different way. People’s attention span become shorter.

When you study politics and you study totalitarianism, you realize that one of the first steps towards totalitarianism is to get the majority, eighty to ninety percent of the population, to think only in an attention span of twenty-four hours. Once you do that, you can take absolute power regardless of your ideology. Whether someone is trying to do that or not, it’s almost like technology could become the totalitarian power itself or someone is just going to say “Hey, this is great, we can just step in and take over” and then you really end up in in your “1984” situation.

The future: “I absolutely love what I’m doing”

Unlike many bands on the electronic scene that celebrate their 25th to 30th anniversary at this point in time, Ronan’s creativity is escalating and building up to a new momentum with “something big” happening with “Noire” during 2019.

Coming back from a near-death experience and getting rid of lots of energy consuming obstacles, Ronan Harris feels better than ever, and for those fans out there that would have thought that VNV Nation are about to start to “wrap up” a long career there’s just one message: it won’t happen in the near future.

You said that something special is going to happen next year, something to do with “Noire”. Has it anything to do with the 25th anniversary since you released your debut album?

- It has nothing to do with celebrations, I don’t really care about that to be honest. This is just about “Noire” so it’s not even a celebration of “Noire” because it won’t even be old enough. But I just feel like the door is open and the gloves are off.

But what is different now from the past?

- It doesn’t mean that I was restricted in the past, it was more that there were lots of tensions in my life; a lot of situations and a lot of other people costing me energy. I sort of made plans five years ago to change a lot of that. Slowly, I was changing my life and getting rid of a lot of things that didn’t really bring me any value and didn’t make me happy, or cost me too much energy. For the last year everything just seems so clear and defined and focused and good.

Let’s say your neighbors are toxic people or they annoy you all the time and now they’re gone. Suddenly that is out of your head and you don’t need to worry about it anymore, it’s a background noise that irritates you and now it’s gone.

I also had to move my studio three times because on the last studio album, “Transnational”, I almost died because of this mold on the walls in the studio. It was an old factory and for some reason the water started coming up through the basement, into the foundations and then into the walls. My mycotoxin level in my blood got to very serious levels but I didn’t know what was wrong with me, I was just sick all the time, and finally one doctor said “I think we should test you for something else”. She tested me for my mycotoxin level and said “Oh, you need to get out now or you going to be dead in about two months or you will suffer permanent injury to the point that you never going to be working again”.

That all changed, I came back from that, I moved my studio and that place was a disaster because another company moved in underneath me and made more noise than anybody should make ever. Then I moved to another place and that just wasn’t going to work out, and then I said “I’m trying too hard, fuck it. I’m going to do this differently”, and now I have my perfect location in Hamburg.

But it was much about finding a better place for myself and cleaning out a lot of things mentally and physically, like situationally, that prevented me from being able to use all my energy.

I loved to work on “Resonance”, it was the most incredible project, just to work with so many incredible musicians. It was an experience of working on a super professional level and that gave me an experience of “I can manage this, I can do this”

Although you don’t do celebrations, next year it’s 25 years since you released “Advance and Follow”. There’s no limit, no best before date, for how long VNV Nation will continue?

- I absolutely love what I’m doing. Here’s a great example: I just released this album where people, who are my critics, finally got this one. I thought “It’s not that the others weren’t”. Just because you get it, it doesn’t mean it’s good or bad, that’s a subjective thing. That is something critics never understand, that it’s truly a subjective experience. But I did this album that seems to have hit a lot of people right where I hoped it would. I really hoped that people would get what I try to say.

I had a guy in here in another interview who said to me something about “Transnational” which a lot of these scene types didn’t get. I said “Sure, that’s OK because it’s actually one of the most popular albums” and he was like “No! Everybody hated it” and I was like “Yeah, the people you’ve talked to and that’s just the small little group that you hang around with in your echo chamber. You don’t met all the other people who liked it and they got something really big out of it”.

With “Transnational” I wanted to do something that’s was a little bit dirty, going back to the roots of how I made electronic music twenty or thirty years ago with a simple sequencer and a sampler, and I did a lot of tracks like that. And I was doing a homage to bands in the eighties that no one had ever heard of, or music from the seventies. All of these things brought me to where I am. In every single song I used sounds out of every VNV Nation album. I told this guy “You didn’t get it because it wasn’t your taste at the time”.

I liked “Automatic”, it had a lot of nice, catchy songs on it, but suddenly a lot of people jumped on that and like “Oh, you make catchy songs” and that’s not why I made it. It’s nice that it’s there but never come and say “Oh, now it’s always going to be like this” because it doesn’t work like that.

I’m not a major label artist, I’m just one guy making what I like and it gives me a feeling that I hope that other people feel in the same way.

Photos for Release by: Mandy Privenau

Read more in Release

“Noire” review

Live report with photos from Partille Arena, Sweden