What

is Japanese noise music? Mattias Huss

went to Japan to find out and wrote

a tedious thesis about it. Here, on

the other hand, is a quick fix of

select impressions from the land of

rising noise.

Koji

Tano of M.S.B.R. with assistant rustling

dry leaves by a microphone during

this autumnal show.

Photo

by: Martin Ekelin

The

ideology of noise

The Sixth Bowels of Noise Festival

(December 13-14, 2003), hiding among

the love hotels in the heart of Shibuya,

Tokyo, would be nigh impossible to

find without the guiding roar issuing

from the building. Here Japanese and

American noise bands clash during

two days, and two cultures along with

them.

American bands Slogun, Control, Richard

Ramirez etc, radiate danger and provocation.

Thoroughly pierced and muscular, they

cling to the political/sexual/provocative

tradition of early industrial and

noise movement. Although Japanese

noise superstar Merzbow could be blamed

for the proliferation of bondage and

porn imagery in the noise genre, Japanese

artists seem to a great degree uninterested

with this ideological burden of noise

music. M.S.B.R.'s Koji Tano is another

of those benign and quiet noise engineers

approaching middle age, who are doing

SOUND, period.

– This is beautiful music for

me, Koji Tano says, referring to his

own mix of pummelling earth quake

bass, roaring motors and high pitched

squeals. There are no specific messages

in it. I just love sounds.

A

temple of noise. Koji Tano's own (vegetable?)

shop with his office at the back.

Photo by: Mattias Huss

The lure of noise

I loved Japanese noise music before

I even heard it. In fact, I probably

liked it much more back then, as an

idea. This was the intelligent person’s

black metal, I reasoned, unendurable

to any ”ordinary” person,

yet somehow highbrow and mysterious

rather than forcedly ”evil”

and handily linked with the old school

industrial scene, which was my territory

anyway. According to the magazines,

there was this bookish guy named Akita

who didn’t talk much, but who

would come out on stage and make,

like, the MOST EXTREME MUSIC IN THE

WORLD. I don’t know what personal

issues I might have had at the time,

but that really appealed to me.

The

corruption of noise

If you want to be a star, you go to

Tokyo. Osaka, on the other hand, serves

as the DIY garage of Japan. Nearby

Kyoto with its then vibrant university

life could probably lay the claim

to be the origin of Japanese noise

music in the seventies, but noisicians

with strong ties to the sprawling,

industrial giant that is Osaka are

numerous. The arguably most important

japanoise label Alchemy Records keeps

its shop there, with noise music’s

finest screamer Masonna as store clerk.

The Bears club, run by former Boredoms

member Seiichi Yamamoto, and other

strange and tiny venues like Bar Noise

saw the early steps of Japanese noise

terror.

– In the beginning no one was

planning anything, Matt Kaufmann remembers,

introducing me to another closet-sized

music pub in Osaka’s Amerika-mura,

a few blocks of second hand clothing

stores, youth street fashion chaos

and record shops. It was like people

were just crazy. They had no image,

no plan. Visits by big indie artists

from abroad were rare at the time,

so when they came everyone went to

see them. There would always be some

Japanese artist warming up, and people

like Masonna or the Boredoms would

just kick the asses of the main performers.

Yamantaka Eye (Boredoms) was remarkable;

he completely turned the way people

thought about music upside down.

Matt Kaufmann has lived in Osaka teaching

English for around 15 years and covered

the scene in fanzines and magazines.

Many agree with his opinion that noise

music grew stale toward the end of

the nineties, when noise bands started

trying to sound like other noise bands,

pursuing stardom (to the extent that

such is possible in this genre) and

generally sacrificing creativity for

easy bucks.

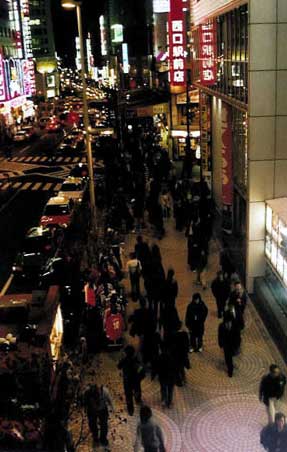

The shopping

and nightlife district Shinjuku in

Tokyo where Tano's ahop is located.

Photo by: Mattias Huss

The

noise boom

Japanese record labels do not promote

Japanese music abroad, or if they

do, they do it badly. The ”Sukiyaki”

song by Kyu Sakamoto topped the billboard

chart in 1963. Since then, Japan has

not made much of an impression in

the mainstream, despite meagre attempts

at marketing female j-pop stars like

Seiko Matsuda and currently Hikaru

Utada in the US.

The Japanese underground, on the other

hand, tends to find its way out by

other channels. Some promotional groundwork

for the sudden burst of japanoise

upon the world was made by musicians

like John Zorn, who fell in love with

Japanese avant garde and started

releasing their music on his own label,

and Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore

who even managed to get a snippet

of Masonna played on MTV. All the

while, a network of dedicated micro

labels around the world made their

best trying to package and release

the maelstrom of material flowing

to them from prolific artists such

as Incapacitants, Hijokaidan, Merzbow

and Aube.

–

There was a kind of noise boom between

1992-1996, Yoshiyuki Hiroshige says.

The leader of legendary noise outfit

Hijokaidan and owner of Alchemy Records,

he saw the sales figures for obscure

noise bands suddenly rise, only to

abruptly fall again when the curiosity

generated mainly in America ran out.

Former

Merzbow-member Kiyoshi Mizutani likes

using natural found sounds. Or should

that be golf?

Photo

by: Martin Ekelin

During this time, the imagery of japanoise,

similar to that prevalent in the power

electronics scene overseas in its

depiction of deviant sexuality, war

and so on, became established thanks

to fanzines, posters and record labels

eagerly promoting the extreme nature

of noise with fitting motifs. This

obscured the fact that a large chunk

of the Japanese noise performers took

their inspiration mainly from psychedelic

music and progressive rock, and cared

little for industrial fringe ideology.

– We just loved the live euphoria

of bands like Deep Purple, Black Sabbath

and Jimi Hendrix, Hiroshige remembers,

trying to explain how the group found

their sound. They would really let

go on stage with massive walls of

feedback and things like that.

What Hijokaidan did was dispensing

with melodies, guitar solos and other

boring staples of the rock giants

and cutting straight to the feedback

and orgasmic release of noise from

broken speakers. They may have been

playing guitars, but to all appearances,

it sounded more like the end of the

world as we know it.

Yuko

Kitamura, or Yuko Nexus6 with her

sound gun is part of the new experimental

electronica movement sometimes called

onkyo.

Photo

by: Martin Ekelin

The

sound of noise

Layers upon layers of simultaneous

sound create a ”pure”,

almost anonymous noise. The sound

simply is, without rhythms, temporal

shifts or any kind of distinguishable

patterns. Yet, even this seemingly

stable wall of noise changes irregularly.

There seems to be no peace here, only

a kind of absolute evolving chaos.

Still, noise can be good or bad to

the individual listener. A good noise

performance will open up with patience,

revealing new dimensions and layers

of significance where you first could

hear nothing but a wall of static.

There is nothing Japanese about it.

In its purest form, noise music all

around the world can be described

like that. With globalisation, a Japanese

style can no longer be discerned,

if that indeed ever was the case.

At its core, what fascinated me most

about japanoise was the concept of

noise music seemingly without a message

or an ideology and the zen-like implications

of that. Wasn’t it actually

a spiritual thing, or maybe an expression

of repressed sexuality, or even a

political protest? It took me a B.A.

thesis to realize that sometimes,

you do that kind of thing just for

the hell of it. It’s fun, plain

and simple.

P.S.

These

days many of the grand old men of

japanoise are softening, moving into

ambient territory, switching from

analogue to digital equipment. Quiet

and introspective experimental electronica,

represented by the onkyo scene, is

bubbling vitally in Japan and around

the world. Oh, and more women are

making noise, globally. Japanoise

is not dead; it’s just changing,

interbreeding with the fertile Japanese

electronic underground and producing

quite remarkable offspring in very

different genres. |